Ordinal numbers

Learning Objectives

🏢 Let’s imagine you’re working in a 10 storey office building. There are 10 different levels. We need a way to describe each level of the building. We start on the ground floor of the building - level with the ground. We use an ordinal number to describe the other levels in the building.

To form the ordinal number we take a number and add the correct

☝🏿 Up from the ground floor, we are then on the 1st floor (first floor) ☝🏽 Up from the 1st floor, we are on the 2nd floor (second floor)

| number | + suffix | = ordinal number |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | st | 1st |

| 2 | nd | 2nd |

What will the ordinal number be for:

a) 21?

b) 40?

c) 49?

d) 13?

Use ordinal numbers to write the days of the month for the following events:

a) Tomorrow b) A week from now c) Easter Sunday 2024 d) When is Eid expected to occur in 2024

- 1st

- 2nd

- 3rd

- 4th

- 5th

- 6th

- 7th

- 8th

- 9th

- 10th

📋 Specification

Let’s consider a function called getOrdinalNumber that needs to work like this:

- it takes one argument - a whole number, like 1, 2, 3, etc

- it returns a string that represents the ordinal number

getOrdinalNumber(1); // returns "1st";

getOrdinalNumber(2); // returns "2nd";

getOrdinalNumber(6); // returns "6th";

The requirements above form a

getOrdinalNumber to behave when it is called with different inputs.

Testing frameworks

Learning Objectives

To help us think about the requirements of getOrdinalNumber, let’s consider one case:

💼 Case 1

const input = 1;

const currentOutput = getOrdinalNumber(input);

const targetOutput = "1st";Case 1 states that when getOrdinalNumber is called with an input of 1, it has a target output of “1st”. Our first step is to check that getOrdinalNumber works as we have stated.

We have used console.assert to write assertions to write tests for our code before. console.assert is a useful building block, but it is limited. Now we will write tests using a

🔑 A test is any piece of code that runs an assertion on the code we’re testing

We want our tests to:

- be easy to write

- be easy to read

- give clear feedback on what the current output is

- give clear feedback on what the target output is

- allows us to easily write multiple test cases

A test framework will help us build test cases like this.

🧑🏽🧑🏿 Dialogue

We can use a short dialogue to think about why we want to use a testing framework:

- 🧑🏽 Büşra

- Ali, looks like I need to implement a function.

- 🧑🏿 Ali

- Cool. How are you going to check it works?

- 🧑🏽 Büşra

- I’m going to use tests to check that the function gives the target output as described in the specification

- 🧑🏿 Ali

- Seems wise. How are you going to write a lot of tests efficiently?

- 🧑🏽 Büşra

- I’m going to use a testing framework to write test cases quickly. The framework will make sure that the tests give fast, reliable feedback.

Starting a project

Learning Objectives

Let’s start a brand new project in a directory called ordinal-testing-example and create a file called package.json in our project.

- Open your terminal and ensure you’re inside the

CYFdirectory you created earlier in the course. - Make a new directory on your local machine called

ordinal-testing-example. - Change directory into

ordinal-testing-exampleand double-check your current working directory.

% pwd

.../CYF/ordinal-testing-example

💡Package

package.json stores useful information about our project, like the name, description, and version. It is written in the JSON format.- Create a

package.jsoninordinal-testing-example. - Make sure it contains a name and description.

👉🏽 Need help? Follow step by step instructions

- Create a

package.jsonfile in your project directory:

touch package.json- Add a name to it like this:

{

"name": "ordinal-testing-example"

}- Add a description:

{

"name": "ordinal-testing-example",

"description": "An example application showing how to write tests using the jest framework"

}We can continue adding more information about our project as the project grows. For now, double-check we only have a package.json in our project:

% ls

package.json

Using packages

Learning Objectives

When writing software, we continually make use of software written by other developers. We can call these

We use packages so that we don’t have to solve every problem ourselves. Other people have often solved some things we need to do really well. Using other people’s solutions to parts of a problem means we can focus our time and effort on what’s special about our problem.

Imagine we wanted to work out what the time is in a user’s city. Instead of writing code to work out the time for every city’s time zone (and when they change!), we can use a package some “city time” experts have written, and which they keep up to date.

Different programming languages give developers different ways of accessing packages for use in their code. We will use

npm, downloads and manages useful packages of code from the npm registry.

Installing Jest

Learning Objectives

Jest is a package used to help us to write and run test cases in JavaScript. Our next step will be to figure out how to install the Jest package on our machine, so that we can use it in our project.

We can find out more about the Jest framework from the documentation online.

In the Getting started section of the documentation, Jest gives us the following command:

npm install jest --save-dev

Let’s break down the different parts of this command.

npm-npmis the package management tool we are using, so we need to run it.install-npmhas a subcommand calledinstall. We use it to download a package from the npm registry onto our machine and install it.jest- this is the name of the package we want to install on our machine.--save-dev- this means the package is needed for development but not needed in production. Our ordinal app doesn’t needjestto run, but we need it to help us develop it.

So overall we can think of this command as saying: “Please go to the npm database, find the Jest package and install it on my local machine”

Let’s execute this command in the same directory as the package.json.

To double check we’re in the correct directory, we can run pwd:

$ pwd

.../CYF/ordinal-testing-example

pwd is telling us we’re in the ordinal-testing-example directory.

We need to double check the package.json is also there too.

$ ls

package.json

Now we can execute the command

npm install --save-dev jestOur project structure will now look as follows:

ordinal-testing-example

├── node_modules

├── package-lock.json

└── package.json

1 directory, 3 filesAfter running the command, we now have a directory called node_modules in our project too.

The

node_modulesdirectory contains all the code from thedependencies🧶 we installed in our project. You won’t need to look inside the🧶 dependenciesA dependency is a package that your project depends upon. node_modulesdirectory - you just need to know it contains the code for Jest and any other dependencies we install in our project.

Running the npm command also updated our package.json file for us:

{

"name": "week-4-test-example",

"description": "An example application showing how to write tests using the jest framework",

"devDependencies": {

"jest": "^29.5.0"

}

}We’ve now got some additional information inside the package.json:

"devDependencies": {

"jest": "^29.5.0"

}✍️🕹️ Follow along

Install Jest on your local machine. Double check you’ve got the correct files and folders written to your local machine.

Jest's Application Programming Interface

Learning Objectives

With Jest installed, we need to figure out how to use the Jest framework to write tests.

This means we need to look at

API stands for

- Application

- Programming

- Interface.

We’ve encountered the word interface already.

But we can break down each word in this acronym to understand it altogether.

An application is a program or piece of software designed to serve some purpose.

Programming refers to the process of writing code or software.

An 🕹️interface is a shared boundary between two or more systems.

We’ve encountered several functions like console.log and Math.round already.

console.log and Math.round are APIs.

console.log is actually implemented in a different language (C++), but that doesn’t matter - its functionality is exposed to us when we write JavaScript, and we don’t need to care how it’s actually implemented or how it works.

Jest provides an API so we can write tests. So we have to find out about the Jest API to start writing tests with Jest.

📝Note

🧐 Other APIs

Try and list other examples of APIs you’ve used since the start of the course. Start a thread in Slack to discuss with your class.

First test case

Learning Objectives

🎯 Goal: Write a test for the case below, using Jest:

Case 1 💼

Our first case is that the ordinal number for 1 should equal "1st".

We can create a file called get-ordinal-number.test.js and write our first test there.

We can use documentation to work out how to write our first test using Jest.

get-ordinal-number.test.js:

test("converts 1 to an ordinal number", function () {});Let’s break down this syntax.

The test function is part of the Jest API, a function we use to perform a particular task.

In particular, we’re using test to create a test case.

Before, we could use Math.round and console.log because Math and console are provided for us by Node.

test isn’t provided by Node, but when we ask Jest to run our tests, it will make sure the test function exists and that our code can use it.

Let’s break down the arguments we’re passing to test:

- 1st argument:

"converts 1 to an ordinal number", a string which describes the behaviour we’re testing for - 2nd argument:

function() {}, we will write some assertions in thisfunction() {}to check the behaviour

⚖️ Creating assertions

We need to write an assertion inside the body of function() {} inside get-ordinal-number.test.js

get-ordinal-number.test.js:

test("converts 1 to an ordinal number", function () {});💡Recall

In this example, we want to check that the following is true:

We expect getOrdinalNumber(1) to be "1st"

An assertion in Jest looks like this:

expect(currentOutput).toEqual(targetOutput);The function toEqual is used to check that the current output of getOrdinalNumber(1) and the target output of "1st" are equal to each other.

toEqual is just one example of a function called a matcher.

A matcher is a function we use to compare values in Jest.

So the whole test looks like this:

test("converts 1 to an ordinal number", function () {

expect(getOrdinalNumber(1)).toEqual("1st");

});👟 Running tests

We can try running the file get-ordinal-number.test.js with node in the following way:

node get-ordinal-number.test.jsbut we get an error:

ReferenceError: test is not definedGoogling “ReferenceError JavaScript”, MDN tells us this is because we’re referring to a variable that doesn’t exist. This is because test isn’t defined anywhere in the file.

We need to execute this file so that the Jest API is available in our file. We can do this by running the test file using Jest: we do this using an npm script.

The “scripts” section of the package.json is where we can write useful commands we’ll use in our project. We can add a “scripts” section to the package.json so that it reads as follows:

| |

Finally, we’ll need to run our tests.

Now we can run the command npm test.

When we execute the command, npm test, we will run npm, and npm will look inside the “scripts” section of the package.json and look up the command for “test” - in this case, “jest”. npm will then run “jest”.

We can’t ourselves just run jest on the command line, because it isn’t installed in a place our terminal knows about. But when npm runs a script, it will make sure all dependencies installed for the project are available.

Interpreting feedback

Learning Objectives

We currently have a project structure like this:

week-4-test-example

├── get-ordinal-number.test.js

├── package.json

├── package-lock.json

└── node_modules

1 directory, 3 filesAnd get-ordinal-number.test.js

looks like this

test("converts 1 to an ordinal number", function () {

expect(getOrdinalNumber(1)).toEqual("1st");

});After running the test above, we should get feedback indicating whether or not the test has passed.

✍️Predict and explain

🚢 Defining the function

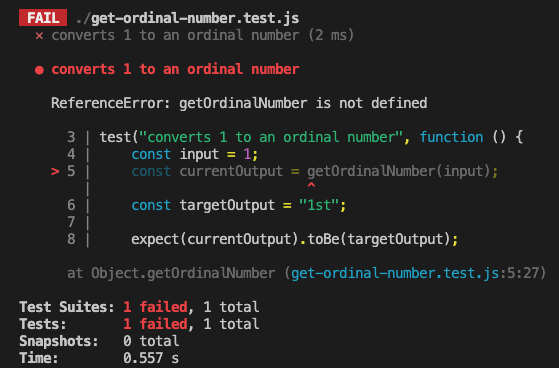

At the moment, our test feedback gives the following:

Just like we saw when the test function wasn’t defined, the test code is throwing a

This means that we haven’t defined a function named getOrdinalNumber, but we’re trying to use it.

To fix this, we can declare getOrdinalNumber.

function getOrdinalNumber() {}

test("converts 1 to an ordinal number", function () {

expect(getOrdinalNumber(1)).toEqual("1st");

});Now we can run the tests again and check the test feedback.

Assertion errors

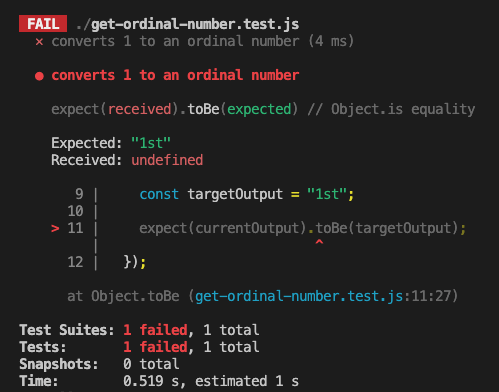

We now get the following feedback:

Jest tells us 3 main things:

- The test case that failed

- The target output and the current output

- The line number where error occurred

Jest defines Expected and Received in the test feedback:

- Expected: “1st”

- Received:

undefined

✍️exercise

What are the values of Expected and Received in the test output?

How do Received and Expected match up with the target output and expected output ?

What line number did the test case fail on?

Avoiding repetition

When we wrote console.assert tests before, we ended up extracting variables because we were re-using values.

Without Jest, this assertion would probably have looked more like:

const input = 1;

const targetOutput = "1st";

const currentOutput = getOrdinalNumber(input);

console.assert(

targetOutput === currentOutput,

`Expected ${targetOutput} but got ${currentOutput}`

);Because Jest makes a useful error message for us telling us what the target and current outputs are, we could write this all in one line. We didn’t need a variable so we could pass "1st" both to getOrdinalNumber and into the message.

Jest helped us to avoid writing more repetitive code.

Passing getOrdinalNumber

We can now pass the test by implementing functionality for the first test case. We could write the following:

get-ordinal-number.test.js:

| |

Dead Code

Learning Objectives

As software engineers, we have a responsibility to build code that not only fulfils the required behaviours of the programme but is part of a well-structured and “clean” codebase.

What is meant by “clean”?

Clean code generally means code that is:

Understandable for other programmers. We achieve this through good variable naming, avoiding chaining too many methods in one line, good choice of syntax depending on the data type being used, etc.

Avoids duplication. Not repeating code where it could be a reusable function, making more efficient choices in our conditional logic, using loops where relevant, etc.

Passes all tests (if you have tests in the repository).

And importantly, contains a minimal amount of “moving parts”. Removing any bulk that isn’t contributing to the behaviour we want to achieve. This means watching out for “dead code”.

Keeping to clean code helps us collaborate better, code more efficiently and accurately, and make programmes more readable.

It means products we build can be maintained in the future without wasting more developer time than necessary trying to work out what the code is doing.

What is meant by “dead” code?

A segment of code that is no longer used.

As a programme evolves there might be many changes, fixes, feature additions made to the code. There is a high probability that when those changes were made to the code, there was no time to “clean” up the existing or old code. This can lead to code being left in the repository that no longer has purpose, whether by accident or on purpose.

One common way to identify dead code in our programmes is by using a

When we remove dead code we can reduce the “bloat” of our code, making it easier to maintain and improving debugging processes. It means we don’t need to read and understand code that isn’t used.

✍️Exercise

📖 Read this more detailed breakdown of dead code from Devopedia: https://devopedia.org/dead-code.

❓ Answer the following questions:

- What makes a piece of code count as “dead code”?

- What is the difference between “redundant code” and “unreachable code”?

- Why do we want to remove “dead code” as much as possible? What are the benefits of removing it?

- What tool makes finding “dead code” in our repositories easiest? (Hint: Do you use this tool already to code?)

💡Tip

In the related backlog item, you will look for dead code in an existing code base and handle it appropriately. Have fun!

Generalising further

Learning Objectives

In English, ordinal numbers mostly follow the same pattern.

Numbers ending in 1 will generally have an ordinal number ending in “st”.

Here are some examples of this pattern,

1st, 11th, 21st, 31st, 41st,…

All the numbers ending in 1 will continue to end in "st", with the exception of 11.

11 is slightly different and ends with a "th".

We can now update our test case to check that getOrdinalNumber works for lots of different numbers ending in 1.

get-ordinal-number.test.js:

| |

We’ve also updated the test description because we’re adding more assertions and checking slightly different functionality.

✍️🔧 Implement

getOrdinalNumber so it passes the test case above.Anonymous functions

Learning Objectives

We have seen functions written like this:

function convertToPercentage(decimalNumber) {

return `${decimalNumber * 100}%`;

}In our Jest test, we wrote a function differently:

function() {

expect(getOrdinalNumber(1)).toEqual("1st");

expect(getOrdinalNumber(11)).toEqual("11th");

expect(getOrdinalNumber(21)).toEqual("21st");

}✍️👀 Spot the difference

We didn’t give a name to the function in our Jest test.

This is ok, because we don’t need it to have a name. We don’t call the function by name. We passed the function as an

test function. The test function takes the function as a

We can imagine the test function is defined like this:

function test(name, testFunction) {

// Call the passed test function

testFunction();

}Inside test our function is labelled with the name testFunction. It would be labelled this whatever we named it before. Even if we didn’t label it ourselves at all, it is still labelled with the name testFunction inside test.

Because it doesn’t matter what we named the function (because we never call it by name), we didn’t give it a name.

Otherwise, these two functions act the same. The only difference between them is whether we created a variable name for the function in the scope where we defined it.

Arrow functions

Learning Objectives

As we write more code, we are going to write lots and lots of

JavaScript has even shorter ways of writing an anonymous function. These four functions all do the same thing:

function convertToPercentage(decimalNumber) {

return `${decimalNumber * 100}%`;

}// We can skip the name of the function if we don't need it to have a name.

function (decimalNumber) {

return `${decimalNumber * 100}%`;

}// We can also skip the keyword 'function'.

// If we do this, we need an arrow between our parameters and the function body.

(decimalNumber) => {

return `${decimalNumber * 100}%`;

};// If our function just returns a single value,

// without needing any other statements in our function,

// we can even skip the return keyword.

(decimalNumber) => `${decimalNumber * 100}%`;This can make it easier and quicker to write functions. It also reduces the number of things we need to read in a function.

Applying all of these techniques, we can rewrite our Jest test with fewer words:

test("works for any number ending in 1", () => {

expect(getOrdinalNumber(1)).toEqual("1st");

expect(getOrdinalNumber(11)).toEqual("11th");

expect(getOrdinalNumber(21)).toEqual("21st");

});It doesn’t matter whether you use arrow functions or use the function keyword - they work the same.

Not all arrow functions are anonymous - you can assign them to a variable too:

const convertToPercentage = (decimalNumber) => `${decimalNumber * 100}%`;Anonymous vs named refers to whether the function is bound to a name, not whether it was defined with the function keyword or an =>.

Testing Workshop

Learning Objectives

To get the most out of this workshop - don’t just watch, code along 💻 You can use the code samples below as a starting point.

Exercise 1

// Create a function that takes three numbers as parameters

// and returns the largest of the three

Exercise 2

- Start with an empty folder

- Create a new NodeJS project:

npm init -y - Install Jest as a dependency:

npm i jest --save-dev - In package.json, change

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"to"test": "jest" - Create a file for our first exercise:

example1.test.js - You can run your tests using

npm test